A series of engaging conversations with and photo essays of renowned photographers who promote the discourse on child protection through their work—photographers who put #ChildhoodInFocus.

For documentary photographer Rohit Jain, it is important that the photos he clicks generate empathy and urge the viewers to act for a cause. His photos of the children living with congenital disorders due to the Bhopal gas tragedy are a testament to his purpose. Fuelled by the passion to tell stories and work towards social development, three times grantee of the Pulitzer Center, Rohit Jain endeavours to bring humanity closer with his photos and the untold stories behind them.

Here, in conversation, he shares about his venture into photography, his experience of working on projects like the Bhopal Gas Tragedy: Eyes Wide Shut, and his views on the impact of gender and caste inequality on children.

1.Your Instagram handle photoforacause, aptly captures the style and subject of your photography. Your goal of telling stories through pictures and your interest in social development is widely known. What remains unknown is your venture into the profession. How did it begin?

Firstly, let me tell you, I am not a trained photographer. It all began in 2010, I wasn’t interested in doing an MBA or a conventional job. I was exploring and trying to find what I wanted to take up as my career. I knew I wanted to do something that would allow me to travel, write, and contribute to social development.

One day, I got a chance to conduct a survey for MGNREGA. I was required to visit a village in Uttar Pradesh for that project. That was my first interaction with rural India, where I witnessed poverty, casteism, poor public healthcare—the ground reality.

Before that, I had only read about these or heard of it from friends. That project was eye opening in every sense.

Once, I saw a child there, he had a swollen leg and was crying in pain. I asked his mother, ‘Why don’t you take him to the doctor? He looks in pain.’ She simply replied, ‘We can’t afford it.’ When I asked where his father was, she said he is a rickshaw puller in Delhi.

Because of the nature of the project, I got the chance to listen to several such stories. It was witnessing incidents such as these that made me think, if I had a camera, I could cover their stories.

The project ended; I took a train to return to Delhi. I reached the New Delhi railway station in the night, and right outside the station, I saw a few rickshaw pullers sleeping in the rickshaws. Instantly, I thought to myself, one of them could be that child’s father. That realization strengthened my intention of covering these stories.

I wasn’t a good writer, but I really wanted to tell the stories behind these faces, which is why and when I picked up photography. I wasn’t passionate about photography; in fact, I didn’t even know how to use a camera.

So it all began with a passion to do something for society, tell real stories, and not with the passion for photography.

Yes, but as I have grown to understand myself, I find this thought of ‘I want to do something for the society’ very egoistic. There’s a lot of ego in that sentence. Instead, I would say, I am doing something for myself, but as an outcome of that, a few stories are being told.

2.What role do children and their stories play in your goal to tell humane stories through pictures?

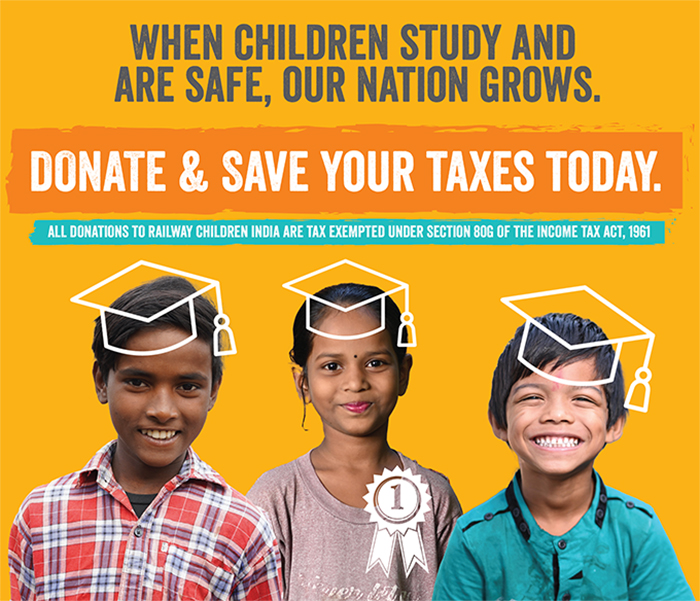

Now, there is a cliché that we hear a lot, children are our country’s future, but we haven’t given our children the space to grow and to be themselves. Right since their childhood, they are burdened with poverty, child marriages, unfair social customs, and orthodox traditions.

The traditions and customs restrict them, especially girls.

Margaret Mead famously said, ‘children must be taught how to think, not what to think,’ but we are going in the opposite direction!

I feel that I received the privilege and the space to think about what I want to become as a person. I have seen patriarchy in my home, I have seen the very specific role of my mother and my father in my home, and I have seen domestic violence. Now, I could have become a violent, patriarchal person because of that, but I got the space to grow and think.

Today, we are not giving that space to our children. All they are being taught is to compete, be ambitious, or for the lesser privileged children, it is the struggle to make ends meet

Now, if a child living at a railway station has to fend for his food, clothing, and survival, if he listens to harsh words from people, if he is abused, he is bound to think that the world is a bad place, that it’s harsh and cruel. This makes him violent, stubborn, and aggressive. The feelings of kindness and compassion take a backseat.

Because of these situations, we lose a child, we a lose human being who could have helped us build a better society.

This reality of children is what I want to show with my work.

3.Your 2018 project ‘Bhopal Gas Tragedy: Eyes Wide Shut’ was trailblazing. How did that project come into being?

So just like everyone else, I had heard of this tragedy in my childhood. More importantly, I used to think of it as a one-off incident. It happened one day, people suffered one day, but it’s history, and now everything must be okay is what I thought.

I visited Bhopal to meet older people who may have witnessed and survived the tragedy and hear from them. Honestly, I didn’t have much of an idea of the impact of the tragedy.

On the first day, I visited the Chingari Trust. It is a rehabilitation centre that provides physiotherapy and other basic facilities to children born with congenital disabilities due to their parents or grandparents having inhaled methyl isocyanate.

When I visited the centre, I saw so many children, all of them born with a congenital disorder, such as muscular dystrophy, cerebral palsy, ADHD. I had not even heard the names of most disorders before that.

I was both shocked and angry. I thought that I had to do something about this. That’s when I began meeting the parents of these children, speaking with the children, visiting their homes. I captured entire days of the children and the parents, and let me tell you, it is not easy.

A child who is living with muscular dystrophy can’t even shoo a mosquito on his own. He can feel the mosquito resting on his arms, but can’t raise his hand to shoo it away or even itch himself. He has to wait for someone to come and itch for him.

Can you imagine how frustrating it must be!

This was the life of 22-year-old Umar. We became good friends during the project and we used to talk a lot. Once I asked him what do you do if you have to pee. He said he would wait either for his mother or for his father to take him to the toilet. I asked what did he do if both his parents were not at home, he said he would wait as much as he could, or he would pee in his pants.

It is hard for us to even imagine, but it is somebody’s reality.

4.It was a special story for the readers. It reminded the nation of a tragedy that continues to haunt generations. How was the story special for you? What were the learnings and challenges you faced while covering that story?

Firstly, I got very inspired and motivated looking at how devotedly and dedicatedly the parents and guardians looked after their children, and even how the kids were coping with everyday challenges.

There was no anger in those households at all!

The only complaint of the parents’ used to be that of their financial condition. They were expecting some kind of support or aid from the Government.

Apart from that, I met Yashi and her mother in 2020, and I think her mother summed it up very well. She said, “Meri beti ko bas bohot saara pyaar chahiye aur badhiya si therapy chahiye.” (All my daughter needs is lots of love and good therapy.)

I would say this is true for all the children. They need constant touch and love, and that really helps them a lot.

As for challenges, my only concern was how to take pictures of the children. Because of their conditions, some of them had saliva drooling from their mouths while the hands of some were contracted. As a society, we haven’t learned how to normalize or accept such expressions. Also, I knew the children wouldn’t like such pictures of themselves either. I didn’t want to compromise their dignity in any way.

Actually, even before I began photographing the children, I spent time in their homes, having long conversations with the parents and the children. In that case, too, if I am asking about the child’s challenges or difficulties to the parents, I would make sure that I am only having such conversations when the child is out of earshot. Because the children know that someone is talking about them, moreover, something about their condition, and they react to such conversations.

I would then move on to speak with the children, ask them something about their favourite food or game. Of course, not many could respond verbally, but they would smile and express their approval.

This way, the children become comfortable having me around, and that’s when I captured them in their happier state. That was about my biggest challenge, or rather how I overcame that challenge.

I learned a lot as a human. I became more aware of the various emotions and feelings that people feel whether it is the perseverance and the unconditional love that parents feel and even how the children keep going at it.

5.Let’s now talk about the follow-up story that you covered during the lockdown. What inspired you to return to Bhopal and re-cover this special story with the pandemic in perspective, this time? And what perspective did you gain about child rights and their violations in India?

Honestly, after the 2018 story, I never thought I would go back there because it was a tough story for me to cover. I also thought that I am not offering much to the children, so why should I return.

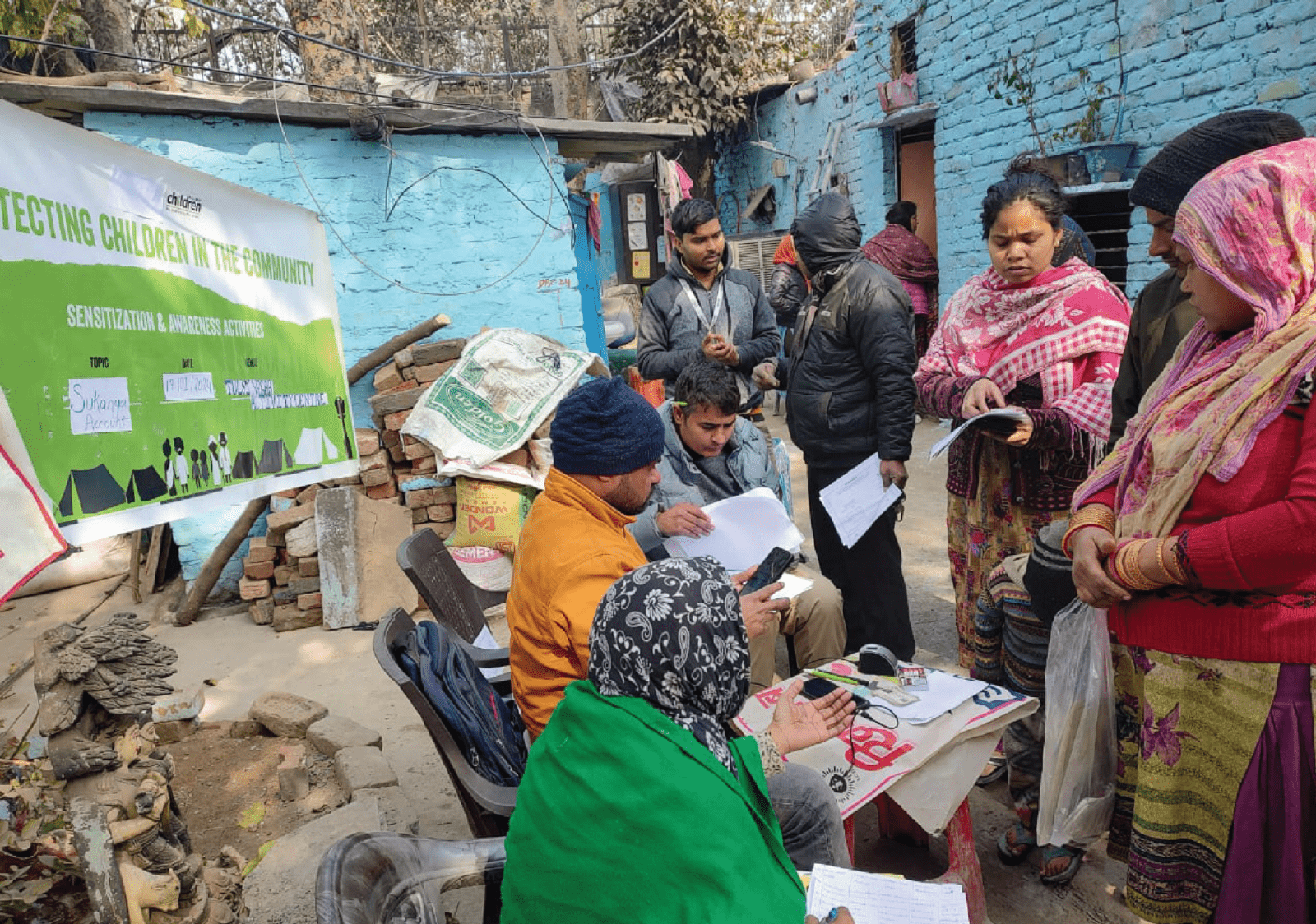

The lockdown happened, and in September, I heard that the children were not receiving therapy anymore. Now, as I mentioned, love and therapy are two things that these children need the most. Therapy saves the child from their condition getting worse. For example, there was a child living with severe autism. With continuous therapy, she could identify that she was hungry and accordingly she would go in the kitchen and sit next to her mother. That would let her mother also know that my child is hungry.

Now, therapy is also of varied kinds. There is occupational therapy, special education therapy, and physiotherapy. Therapy brings a lot of change in children. When they don’t receive therapy, they become half of themselves. The therapists talk to the children, engage them in creative activities, and take them to visit the recreational centre. All of these things contribute to develop their senses and reduce their fears.

Now, if a child is scared of stepping downstairs, they will learn to be less afraid of stairs at therapy. If the therapy stops for six months, their fear returns.

I knew of the importance of therapy in their lives, which is why I went back when I came to know that therapy had stopped for these kids..

Again, I reached out to Chingari Trust. They said that they were going to the house of each child once a week, but that wasn’t very effective. The parents also mentioned that their children had gone one year behind. They had become half of what they used to be. Most of the families were not financially well off, either. Consequently, the diet of the children was also affected.

All of these challenges that the children and the families faced are what I went to cover in 2020.

As for my perspective on child rights, I think no one cares about it. Only the parents and the people at Chingari Trust care for them. For everyone else, it is only an incident that happened back in 1984. Nobody pays attention to the children who are facing the consequences even 37 years later. It is a big issue and a big concern, but nobody is paying any attention. The relatives of these families also discriminate between the children. The children and their parents are not invited to functions; the children are thought of as a jinx.

The violation extends to lack of medical facilities too. There are a few dedicated hospitals for victims of the Bhopal Gas Tragedy, but those hospitals don’t even have a dedicated department for children.

6.Recently, you shared a heart-warming video under your series ‘Khel Khel Mein.’ We see children of the Mushahar community in Bihar being introduced to a camera and their innocent reactions thereafter. We think the video gives an insight into an important, oft-neglected issue, the impact of caste inequity on children. Please share your thoughts or any stories you may have covered on this subject.

What I observed is that when one is constantly neglected and dominated by the upper caste society, when one continually lacks financial resources and basic amenities, one forgets the meaning of dignity. They forget the meaning of living a healthy life.

Let me share an example in the context of the children in Mushahar. There was a family, the child in the family had a runny nose, his nose was blocked, and he was having trouble breathing. I asked his father that he had access to a hand pump, why didn’t he just bathe his son, and have his nose cleaned?

One may think, yes, bathing doesn’t see one’s financial situation, if one has access to water, one can surely bathe. But that is not true.

If one is feeling neglected, one is feeling inferior, if one’s mental health is taking a beating, one will not feel any confidence in one’s life. One will feel that no one cares about me, how does it matter whether or not I have a bath. If you are continually exploited, you will not have the will to live a happy, dignified life.

That’s what is happening in the lives of these kids.

Forget a bath, or hygiene, or even treating pneumonia for that matter, they think that the fact that they get food every day is a huge privilege.

I have another tradition or story to share from Rajasthan. There, Thakurs or upper caste communities live adjacent to scheduled caste communities such as Bhils. Now, during wedding processions in the Bhil community, it is customary for the groom to step down from the horse while passing by the homes of the upper caste. This is all happening in today’s times.

The children witness all these societal norms. They understand the gap in the lives of the upper castes and the lives of their parents. Naturally, this affects their outlook towards living life. They lose the zeal and the confidence to live life. They know, they have to go, work, wage labour, and fear the upper castes.

7.From the girls in Rajasthan playing football to the girls in Aravali playing volleyball, you have captured some truly empowering stories of girls gaining confidence from sports. What is it about playing a team sport that is empowering young girls to break the society-imposed shackles and find their voice?

Now, of course, patriarchy is prevalent everywhere, but more so in places like Rajasthan. The girls living in the villages of the Ajmer district, where I covered their story, faced many restrictions. They would barely get a chance to step out of the village, walk freely like the boys, or even laugh with abandon. They were not even given the space to meet other girls in a group, share personal stories, or even express themselves.

Now, football enters their life! To begin with, they couldn’t believe that they could also be good at this sport. They were told that it’s a boy’s game. Moreover, it is very difficult for anyone in the village, or even in the city for that matter, to accept the image of girls running around in an open ground!

It is a common image for us, having lived a fairly liberal life, but for people who are used to seeing women in a parda, that visual is difficult to accept.

For the girls, though, running was like flying. It gave them a rush in their blood. It made them feel alive, that they are somebody, that they can achieve something. The sport gave them a chance to release themselves on the ground. They would shout, cry, and be ecstatic when they hit a goal.

For somebody who had never stepped out of the village, football allowed the girls to go play in Noida and Lucknow—miles away from their villages. The liberty of playing in a pair of shorts and a t-shirt gave them confidence.

There’s an interesting bit, though, I asked them if they felt attracted to the boys. They replied saying, yes, they did, but they emphasized that they were creating a path for the other girls in the village to follow. They didn’t want to give the villagers a chance to question them. They had to set a precedent in their village so that other girls get the chance to step out of the village and study.

8.Lastly, how do you believe that photos/visuals impact change? How do you believe we can use images as an advocacy tool for child rights across the world?

I always want to achieve two purposes with my work. Firstly, I question, how can my work generate empathy among the people? Secondly, how can it make them take action? I try to understand and showcase the nuances and intricacies of the circumstances, emotions, and the connection of the people in society and nature. I think this is how photography can be used as an advocacy for tool for child rights.