A series of engaging conversations with and photo essays of renowned photographers who promote the discourse on child protection through their work—photographers who put #ChildhoodInFocus.

Whether it is the spirited candid photos of street children in Street Dreams, capturing the familial bond between boys living together in a shelter home in Home Street Home, or celebrating the carefree abandon of childhood in Bachpan, Vicky Roy’s nuanced perspective towards his past experiences and life is spectacularly reflected in each of his stellar projects.

But the success he witnesses today, didn’t come without the strife he faced then.

Vicky Roy fled from his abusive home in West Bengal as a young boy. He reached New Delhi Railway Station with no plan. He picked rags, washed dishes at a dhaba, and lived off the streets in Delhi. One day, fate finally favoured young Vicky, when a volunteer at the Salaam Balak Trust rescued him. At the trust home, began Vicky’s tryst with photography, which continues to win him accolades and recognition as an international photographer.

“When I used to live on the streets, many would have looked at me with pity, but I have always looked at that those days as my most carefree, fun days,” shares Vicky Roy in a conversation about life on the streets, photography, children, and their rights.

1.Yours has been an extraordinary journey from strife to success. How have your life experiences influenced your work?

Interesting question! There are many photographers clicking many photos, but what makes each photograph unique is the photographer’s background. Many a time their place of birth and the surroundings they grew up in influence their thoughts. Same is the case with me. I have experienced life on the streets, I have lived in a shelter home, I have even experienced a professional photographer’s life, and all of these experiences definitely reflect in my work, whether it’s Street Dreams, Bachpan, or Home Street Home. I use my experiences in my work.

For instance, when I was younger than 18 years, I used to live on the streets; therefore, while shooting for Street Dreams, I knew for sure that I would shoot only children below the age of 18. I made that decision because I wanted to narrate the story of my life on the streets, when I was younger than 18, through their pictures.

The influence of my experiences on my photos is very evident.

2.You have captured street children and underprivileged children for your projects ‘Street Dreams’ and ‘Bachpan.’ You’ve mentioned how you shot for those projects with an insider’s perspective. How did that perspective help you in capturing such vivid images?

Time is important to me. How much time has one spent on any project is important. These projects were not the kind where one simply visited, clicked the button, took photos, and returned. Now, if you look at Street Dreams, I remember the name of each child involved in the project. I also know where half of them are base currently and what they are doing.

In Street Dreams, I captured a girl selling balloons; her name was Laachi. She passed away, she is no more, but I know that her daughter still lives with her nani near Hanuman Mandir.

In the same series, there is a photo of two children selling newspapers; one of them is Mangal Nandlal, he is currently working at a restaurant behind the India Habitat Centre.

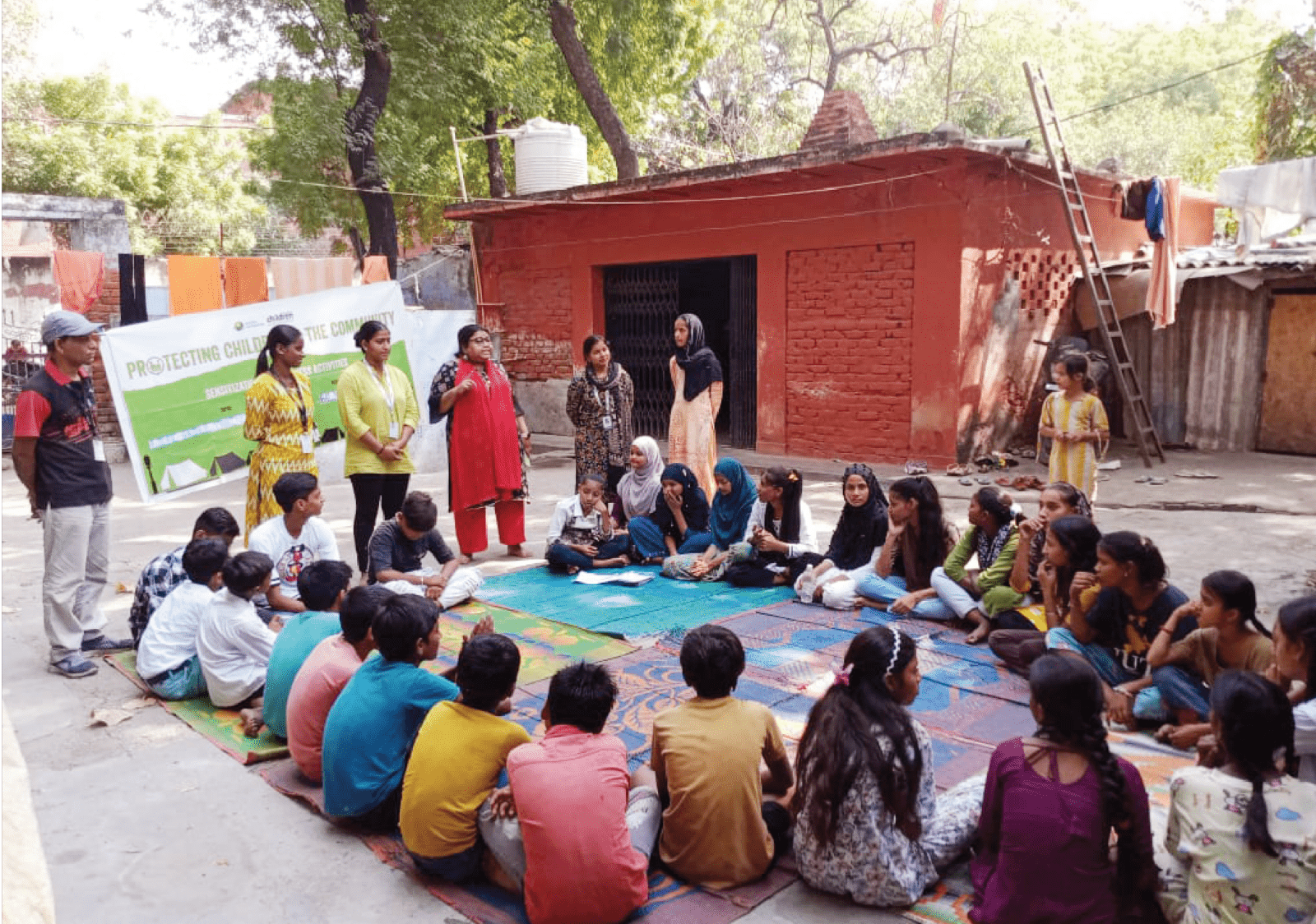

You see, that’s where the insider perspective helps. I have spent time with all the children. Also, I didn’t simply begin clicking as soon as I met them. Street Dreams was shot from 2005 to 2008; during this time, I played carrom with them, I treated them to ice cream in the evenings spent at Connaught Place, and sometimes I would take out my camera and capture them.

This is why I think if one looks at the photos in Street Dreams, one can never feel that the kids have been made to pose.

Now, as for Bachpan. My childhood was spent in abject poverty, but today, I see something peculiar in most urban childhoods. If a kid is free, he/she won’t step out and play in the park; they play on gadgets, nowadays. Alternatively, they play with some other object at home, but most often, that object suffices for only one child.

In my childhood, however, the one spent in poverty, playtime was starkly different.

If my friends and I wanted to play cricket, we would gather a wooden plank, tie a lot of plastic together to make a ball, and there! That would be enough for 8-10 of us. We’d have fun together jumping in ponds. There was no need for any equipment or investing money to play.

That’s what you will see in Bachpan. Children climbing atop trees, waving at a distant train. They are the ones truly living their childhood.

3.You have stated that you do not aim to shock the viewer by painting a bleak picture of despair or point fingers at others for their apathy. How do you walk the tightrope of steering clear of confrontation, yet arousing an emotion with your telling pictures?

I borrowed this balance from my experience.

When I used to live on the streets, many would have looked at me with pity, but I have always looked at that those days as my most carefree, fun days.

We could sleep as long as we wanted; there was nobody to nag us. We could have a shower when and where we wished. The leftover from the Rajdhani/Shatabdi trains was our happy meal. I truly feel that I enjoyed that life.

This is why I clicked the photos in such a way that people do not feel pity for the children. Whatever is their life, they are enjoying it.

In fact, think about it. Why do children run away from the shelter homes that come under the Child Welfare Committee (CWC)?

The primary reason for children running away is that they are used to freedom. Suddenly, in the shelter, they are being disciplined to wake up early at 6 am, shower, and get ready by a certain time. The kids are not able to accept this rude shock.

All of CWC’s shelters have become jails, and no one likes being in jail.

4.Did you ever tell any of the children that you were once one of them? If yes, what were their reactions?

While shooting for Bachpan, no, since we shot at multiple locations with groups of children playing. While shooting for Street Dreams, I did not have a success story back then. We are talking about 2007, here. However, when the project was completed and I set up my exhibition, I did invite those kids to see the exhibition at the India Habitat Centre. They were very happy. They had a gala time with good food on offer. They were also teasing each other ‘Look, your photo’s up there’

I was also slightly worried at that time that they would leave a stain on the completely white walls of a rented gallery! However, they had a great time.

Typically, children don’t live on a particular street for too long, which is why I didn’t get a chance to have that kind of conversation with any of those kids. However, I have done over 500 talks on this topic, all with a single purpose of changing people’s perspectives about street children.

I take time to build relations, therefore, there weren’t any deep bonds formed, but we were friendly with each other. I would play with them, without worrying about my clothes getting soiled.

5.The term ‘invisible’ is very commonly used when describing street children. They are everywhere, yet go completely unnoticed. Your campaigns/projects put them centre stage. How did they feel about being specifically photographed?

Whether it’s a street child or somebody else, everyone loves getting photographed. As I mentioned, shooting for Street Dreams was very sporadic, but for Bachpan, when the kids would see me with a camera, they would get really excited and say ‘I can hang upside down on the tree, capture me doing that.’

Once, I was shooting near Jama Masjid for Bachpan. It began with me capturing two children playing, but when the other kids saw me holding a camera, they also joined, wanting to be clicked. None of the kids were camera shy.

6.You’ve emphasized the troubles of getting legal IDs made for street children. Please elaborate on that issue. What are the troubles they face? How does it affect their future?

We would always find ourselves very vulnerable without a legal ID. It’s a very big issue.

I remember when I was in the shelter home; I didn’t have any ID other than my school ID. Aadhar Cards were non-existent at that point. The only government-issued IDs were PAN Card, Voter ID Card, and a passport.

One day, a few of us from the shelter filled the application and headed to the centre to get our Voter ID card issued. There was a serpentine queue at the centre. A gentleman at the centre noticed that there was a group of similar-aged boys waiting in the queue. He called out ‘Oye, kahan se aaye ho?’ (Hey, where have you come from?)

One of the boys from our group told him that we all stay at a shelter run by Salaam Balak Trust. After hearing this, he asked us to call somebody from the trust, maybe to verify. We called a staff member from the trust; he explained our background to the gentleman.

The gentleman at the centre then, kindly, arranged for a separate queue for all of us boys. Some people waiting in the queue objected to this special treatment. He rebuked those people saying all of you have something called a family; these children have nobody. Somebody has to step up to help them.

Getting my passport issued was another roller coaster. The cops wouldn’t accept Salaam Balak Trust’s address as mine. I was asked to open a bank account then, but that wasn’t smooth sailing either. I was asked to get an affidavit made for the bank account, and then I had to wait for 6 months to apply for a passport, and so on.

There was a hurdle at each step. I lost confidence.

This is why I was doubly excited for taking on #TheInvisibles project for Save the Children. Once again, I was working on something that I have experienced personally.

7.How does the medium of photography drive awareness and change particularly for child rights violations? And do you plan to return to the streets for a new project?

Not only photography but also many other mediums drive awareness and can be used to bring change. For instance, people write to convey their stories. However, photography can sometimes play a more important role because the medium directly mirrors reality. One doesn’t need to read; one can directly see and understand.

Photography has also historically played a role in policymaking. Not many people might be aware but some of the photos taken by Lewins Hine, documenting the working conditions of children in America, helped bring about reforms in the child labour laws.

As for returning to the streets, I’ll go where life takes me. I do many shoots for NGOs, so definitely, if I am approached for an interesting project, I would love to take it up.

8. What would your message be for the young Vicky Roy in the shelter or the many aspiring Vicky Roys across streets and shelters in India?

My only message is there is no shortcut. Now, I know everyone says that, but this is what I would really tell my younger self or to other aspiring boys. If you want to be a ‘lambi race ka ghoda’ or want to stick around for the long haul, you will have to commit to long days of struggle and learning.

For instance, an engineer commits 4 years to learning theory, and 1 year as an intern understanding the practical aspect. That is a total of 5 years before he/she actually begins their career. I think, similarly, a photographer must devote 5 years to learn the art. After 5 years, once they’ve understood the A-Z of the art, they are good to go.

If one has done a 6-month course and calls oneself a photographer, I don’t think one can sustain in the long haul. One must devote time. With that, one must also stop complaining about all the equipment that they are lacking. Those equipments are only useful at a much later stage.

Think about it, when we listen to a singer sing, we don’t ask which mic did the singer use. We appreciate the singer for his/her voice and talent.

Similarly, a photographer shouldn’t get too tied up with trivial things like a lens. Their focus must be on narrating their own story in their unique style, which can be done with a phone camera too. It will take some time to get your hands on that equipment, but you will get it for sure.

9.Photos/visuals help give children a voice. How do you believe that photos/ visuals impact change? How do you believe we can use images as an advocacy tool for child rights across the world?

I am not sure if I have an exact answer for that, but there is one area where I feel photography can be of use.

If you find a lost child and provide shelter to that child through an NGO, there’s a rule, whereby the CWC orders for the child to be sent back to his/her parents, even if there is a single parent. I believe this a failing approach.

Why do I say that? I got a chance to speak with an NGO’s representative while shooting for #Invisible. He said that earlier, we would dedicate 90% of our time getting to know the child and the remaining 10% of our time on administrative work; however, in the current scenario, we spend 80% of our time reporting and completing other administrative work and 10% of our time with the child. Now, that is still okay, but the CWC simply orders for the child to be sent back home. Once the child is sent back home, 80% to 90% of the time, you will find the child back on the streets within 6 months.

Now, how to communicate this journey using photography is something that will need collaboration with NGOs, but it is definitely an opportunity in waiting.