“Who is the first respondent in any child protection issue? It is the community!” says John Bosk, Railway Children India’s lead for Programmes, who shares in great detail RCI’s inspiration behind our community-based work, the scale and scope for the future, and inspiring stories of impact from children and families.

Q) Tell us a little about Railway Children India’s (RCI’s) community work, when and how did it begin?

Ans: During the pandemic, railway stations had shut down completely, and as a result, so had RCI’s operations at the stations. Our outreach work had stopped; our Child Help Desks at the stations were not operational anymore. It was around this time that we began expanding our work to the communities around the railway stations.

We had found in our previous need assessments studies that most of the children rescued from railway stations lived in slums adjoining the stations. These communities, essentially, depend on the railway stations for their livelihood.

When railway stations shut down, all these families were gravely affected. They had lost their livelihoods. Naturally, the children were also deeply affected by this crisis. Our team took note of this situation and began taking relief measures.

Initially, the Railway Protection Force (RPF) had begun distributing cooked meals to these communities; however, those measures were short lived and the communities were soon left helpless. This is when RCI stepped in, realizing an urgent need for support.

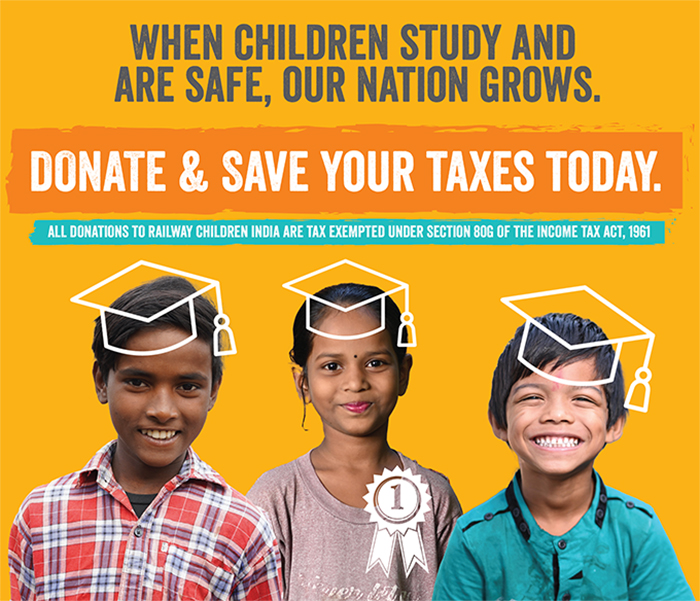

Our intention was to keep the children in the communities safe and to reduce their vulnerability, so that ill-intentioned people do not take advantage of their situation.

We began working with these communities around April 2020. We systemized our interventions in July 2020. We assessed our resources and limitations and the immediate needs of the people, resulting in standardized community intervention across all 10 locations. We referred to it as our Redeployment Plan since we redeployed our staff from the railway stations to the communities.

Q) What’s the scale of the community work? Why did RCI select these communities to work with?

Ans: We are currently conducting these interventions around 10 railway stations—Delhi, Ghaziabad, Bhubaneswar, Raipur, Darbhanga, Dadar, Salem, Trichy, Viluppuram, and Katpadi—that is 30 slums, spread across 7 states.

Beginning from April 2020, we have reached out to a total population of 34,777, which includes 17,574 children and have provided support to 6,019 homes.

The primary reason to work with these communities is that they live around the stations. These slums are at a mere distance of 100 to 200 meters from the station. The close proximity of these communities to the station made us naturally veer towards them.

Q) What have been some of the key findings of the vulnerability assessment conducted across the communities?

Ans: The first major issue that was reflected among all the communities was the loss of livelihood. People in these communities are daily wage labourers, and due to the pandemic, all of them had lost their source of income. Naturally, when the income stops, the whole family is gravely affected. There is lack of food, which soon leads to malnourishment. Consequently, the children in the family are forced to beg or start picking rags for a living.

The second most commonly recurring issue was that the children had begun dropping out of schools. Schools had shut down and had moved to conducting their classes online. Children from these communities did not have access to online education. Additionally, most of the families were migrants. They did not have sufficient documents to enrol their children in schools. Even though the RTE Act states that children being enrolled until the eighth grade need not produce any documents, the ground reality is starkly different. Schools demand documents, which these migrant families were unable to furnish.

Next, we observed rampant substance abuse among children. Lack of access to clean drinking water, sanitation, and a general sense of safety were some other issues that we come out.

Q) Share with us some activities and strategies adopted by RCI to address the child protection issues within communities?

Ans: We found that the immediate need of these families was food. With the help of our local partners, we mobilized some funds and began distributing dry ration to the families. We went a step further and connected the families with social security schemes, like the Public Distribution System. These schemes would prove helpful in the long run since the families would receive food grains and other dry ration from the Government each month.

Next, we took to tackling the gaps in formal education. We visited schools, held discussions with headmasters and teachers, in order to help the children get enrolled in schools. We facilitated government-issued identity cards for the families. For some older children, who had been out of school for a long time, aged 15 to 16 years, we facilitated vocational skill training.

In addition to looking after each child’s specific needs, we extended counselling support to each child knowing well that mental health was a key fall out of lockdown. Keeping the pandemic in mind, we regularly distributed Covid-19 prevention essentials such as masks, sanitizers, etc.

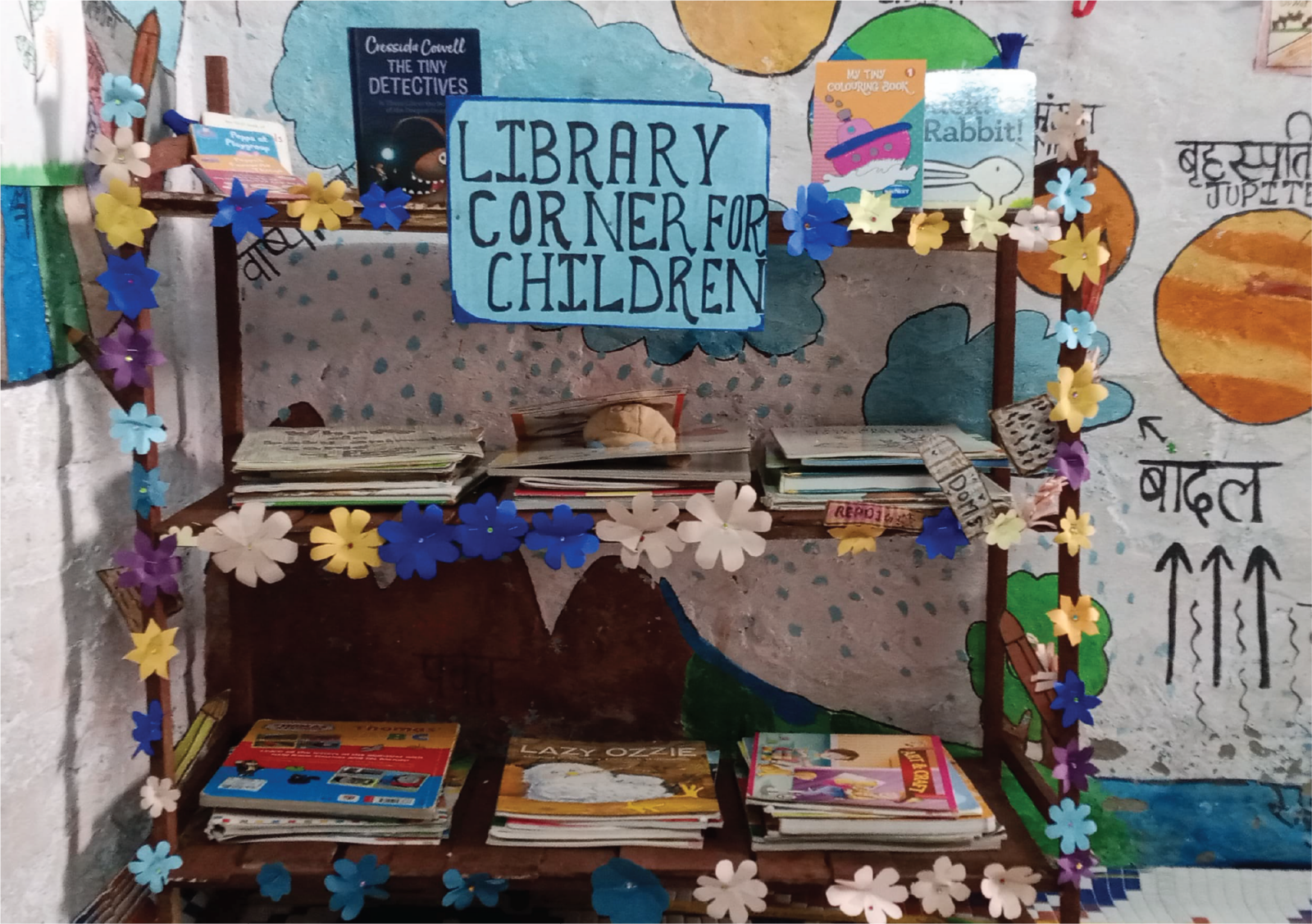

With time, we saw normalcy returning in their lives. By this time, our intervention had upgraded too, becoming more structured and organized. In a few weeks’ time, we piloted our community-based Activity Learning Centres, whereby we conducted classes and sessions for the children.

Looking forward, we plan to organize and form Children’s Groups or Child Protection Committees in these slums. With these committees, we intend to sustain our program and to create a Response System for children. This will help children report any untoward instances or simply get the support that they are looking for and prevent them for facing further vulnerabilities. The committee could also aid in catalyzing community efforts to solve some of their issues such as lack of sanitation or clean drinking water.

Q) What changes have you seen in the community after the commencement of the programme?

Ans: The key change that we observed in the community is that initially, owing to the sudden loss of their livelihoods, they were at the receiving end. They had a basic need of food that needed instant attention; they weren’t thinking beyond that. However, when the community members witnessed our team’s multifaceted efforts, they realized that there is something beyond asking for dry ration. They began requesting for more.

They began requesting for formal education for their children; they requested to be linked to social security schemes; they requested vocational training for the older children.

The underlining change was that, earlier, these families were compelled to send their children to beg and pickup rags; however, with our intervention, the same families wanted their children to, now, attend school.

Among the children, too, we could see positive behavioural changes. They willingly wanted to continue studying; they attended classes regularly. We had introduced certain hygiene practices in the community; we could see that the children were religiously following those practices in their routine.

I would like to elaborate on our intervention in Katpadi. A nomadic community was stranded in Katpadi due to the nationwide lockdown. As a part of our outreach, we connected with them. Children from this community had never attended schools. We began interacting with the children and got them enrolled in our activity centres. We began with kindergarten basics such as alphabets and numbers. Steadily, the parents began showing an interest and agreed to send their children to school and by June this year, nearly 50% to 70% of the children from that nomadic community would have been enrolled in schools.

From never attending schools to majority children of the community attending schools!

Another change that we could catalyse was extending district-level Child Protection Committees to village-level committees in Salem. With this change, we could prevent several child marriages.

Q) How do you believe communities can play a big role in addressing the larger child protection mandate in India? Illustrate with examples.

Ans: Who is the first respondent in any child protection issue? It is the community. For instance, if a child marriage is taking place, the neighbours will know of it. With the correct information, a community can prevent all types of abuses meted out on a child. When a community is negligent towards these issues, even outsiders cannot be of much help. Of course, the child will get help from outside, but only after the incident has already taken place. In contrast, a community can prevent incidents from taking place.

The community interventions that we are conducting are to focus more on prevention and to create safe spaces where children can report any incidents. Prevention and response both lie within the community.

We are all aware of the term child-friendly spaces, but those spaces are only possible when the community is aware and proactive. For instance, take the nomadic communities that we spoke about. In their case, it was the community’s collective decision to send their children to school. Once they were certain that formal education can help their children lead better lives, they agreed to enroll their children in schools.

These key decisions depend on the community. If the community does not allow getting an education, then the child will have no future. He will be left to beg or resort to rag picking. This continues as a vicious cycle from one generation to another. We need interventions such as ours to break these cycles. With our community outreach programs, we intend to break these cycles in order to provide the children with the rightful access to education, nutrition, and protection.