“There is exploitative labour, which children should not be made to engage in. But some other forms of work experiences can be positive,” says Kavita Ratna, who needs no introduction.

As an integral part of Concerned for Working Children (CWC), she has always advocated that a blanket ban on child labour does not address the root causes of the issue; that local governments and systems need to be ignited and collaborated with, for the rights of children to be realised, and that children’s voices are central to paving the way forward on child labour.

CWC’s work on the frontlines and it’s perspective on child labour has been critical in shaping the narrative on child labour in India and across the world. Read on to know their thoughts on child labour today.

Q) The economy has been dramatically affected with the coming of Covid19. Children have and continue to be part of the country’s workforce. How does the current scenario impact the fight against child labour in India/ world over?

Ans: There have been various factors responsible for child labour, which can be divided into pull factors and push factors. Pull factors include economic conditions, particularly, the financial needs of the families. However, there are also push factors, such as the poor quality of education, in terms of the process of learning as well as its subsequent outcomes for children. During or even after the pandemic, both the pull and push factors are/will be aggravated. For example, schools have closed down, and migrant families have gone back to their homes, away from where the children were going to school. These push-pull factors are not new, but have been further aggravated in current circumstances, and so become key concerns. These have placed families in even more precarious positions, where they lose their bargaining power due to their circumstances. This will ultimately lead to further violations of their own rights and the rights of their child.

Q) The Child Labour Act, 1986 has loopholes that have been debated and dissected for years. How do you believe the law needs to be strengthened to deal with child labour? & The role of civil society, local governments and communities, coming together has always been a gap area in ensuring children are safe and protected. How do you believe that can help in thwarting child labour in India?

Ans: Let me just start with a little bit of history. My organisation, CWC, was a prime mover when the Child Labour Act, 1986 came into being. We were directly working with working children and their union , to empower them to organise themselves and to identify, and address , their problems. In the context of child labour, we do not believe all work is good or bad. There is exploitative labour, which children should not be made to engage in. But some other forms of work experiences can be positive. In 1985, we were looking to distinguish between work which ‘enables’ children and work which ‘exploits’ children. We needed to ensure that the positive work children are engaged in, are recognised as a learning experiences. The biggest problem in the law, and even outside of it, is that enabling work of children is not recognised or enhanced. We have always looked at how education and enabling work can go hand in hand. The original Bill for the Act included this aspect. But by the time the Bill came through as Act, it was very distorted, and didn’t serve the purpose it was intended for

During the recent amendment to the Child Labour Act, 1986, we emphasised that we don’t want to amend the Act but to repel and re-enact it. . We believe the has Act failed children. It has not helped in any way, and the number of child labourers has only been increasing. Bhima Sangha, the union for working children, gave their valuable suggestions on child labour , that there can be no ‘universal’ solutions , and that children need to be spoken to and asked their opinion on matters that involve them. Let’s take the example of children living in villages – If we do not consult them, how will we ascertain what they want? If they want to work, what kind of work do they wish to do? The problem is not only the content of the Act, but how we perceive working children.

In various countries outside of India, children beyond a certain age are encouraged to work. For example in America, once a child is 14 years old, he or she is encouraged to work for pocket money. In fact, quite a few students abroad support themselves and pay for their education themselves too, by taking on work. In those countries, the Govt. has ensured certain guidelines to maintain the safety of children in their workspace, and have defined work that enhances the learning of the child in the workplace too. India, on the other hand, has created a stigma around working children

In India, there are a lot of children who work and support their own education, and require learning opportunities along with their work. The Act does not facilitate such solutions.. Quite a few children have their names enrolled at school, but do not actually attend. If they are reported, then the onus falls on the Education Department, but they are not able to manage or answer for the absenteeism in school. Another concern is the stigma around child labour. No child wishes to come forth and say that they are working, because that child will be criminalised, and if the child doesn’t come forward and speak up, then we are unable to intervene and help them. As a result, most stakeholders do not come forward and speak up about working children, be it the government, the parents, employers or even school authorities.

You will notice that as an organization, we have always opposed anti-child labour messages and public engagement which are counterproductive to children, including the perception of the ILO. Our campaign says ‘Let Anti-Child Labour not be Anti-Child,’ that summarises our stand on campaigns which address child labour.

We have spoken to children at railway stations who have ‘run away’ and have chosen to not approach organisations for help. We have found that quite a few children were not ‘unaccompanied’, and have been in constant touch with their families. Quite a few children had their families staying nearby, and were actually living on the platforms because their work was on the platforms and their homes were away

So the perception that most children on the railways were run-aways and have to be re-united with their families in the villages is a faulty notion – and this notion forms the basis for most responses to children in contact with railways. There are many such perceptions about working children which have to be challenged.

The Child Labour Act has a history of failure and has not befitted children. The present version of the Act provides for safe work for adolescents. But it does not provide adequate safeguards for their work – so it is likely to create a labour force which is young, disempowered and easy to manipulate. The Act also does not provide for adolescents to learn while they work and make ensure provisions for that.

Q) For children currently engaged in labour. What unique problems has Covid19 brought?

Ans: In all emergency situations such as a pandemic, there are always circumstances where the children have had to work more than they do otherwise, and it has been a pattern noticed across the world. However, in the current scenario where are the jobs? Most families have gone back to their homes in villages, where there are no job opportunities. They rely on the MNREGA for opportunities, but jobs under the programme are not available for children under 18, though MNREGA could provide them safe work which can be well monitored. It is in fact easier in smaller cities and villages to provide safe work for adolescents than in large cities. We are looking into whether during these times adolescents can be provided with vocations along with access to schools and colleges, to use their time constructively. We have to open all doors for children, because children will continue to do everything they need to, to survive.

Q) Highlight your approach to responding and protecting children during and after covid19.

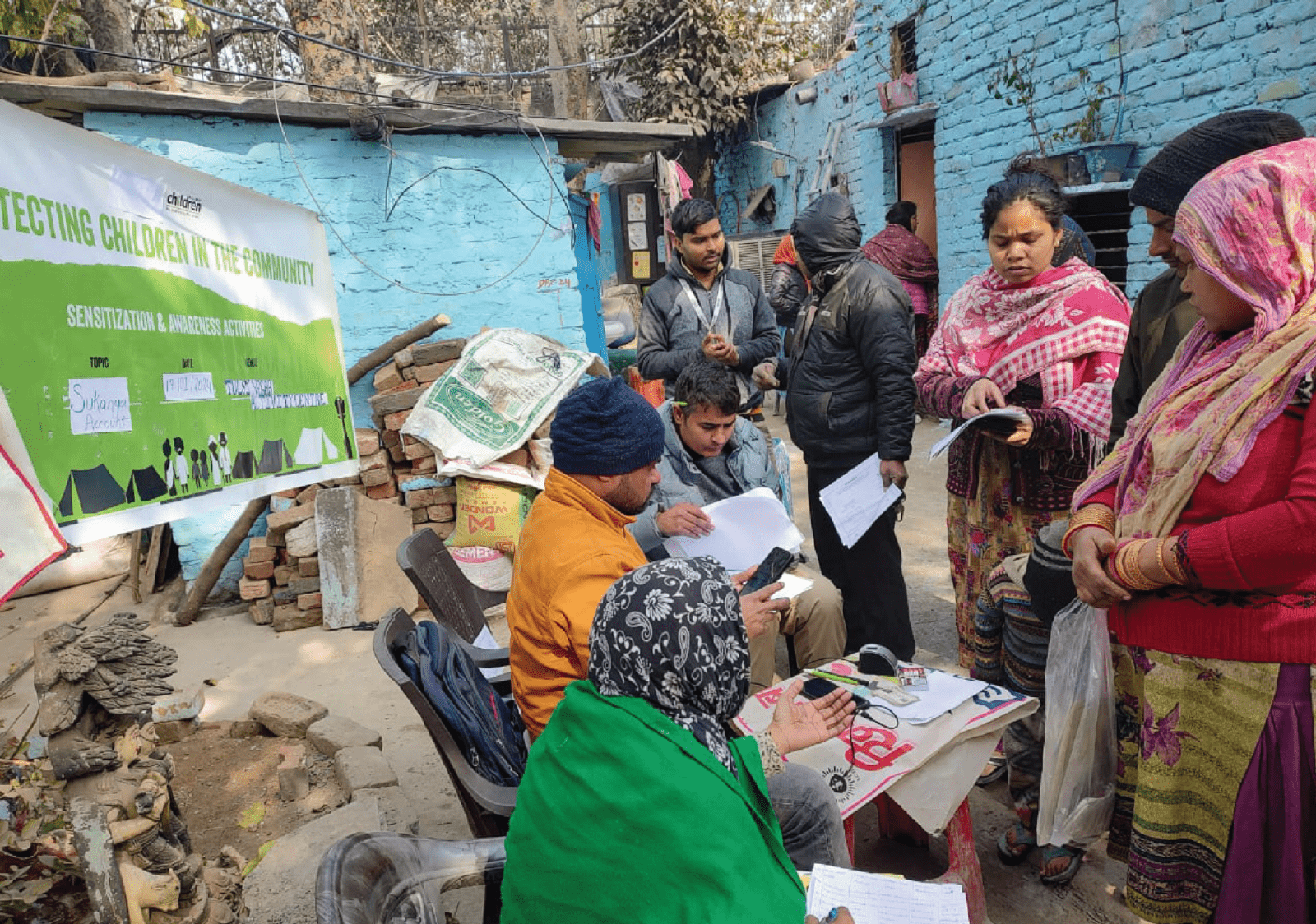

Ans: Our work is multi-pronged. Our approach is to collaborate directly with the Panchayats, children and local communities, and escalate the issues to the state level if required and if the matter has policy implications. If there is an urgent need for immediate response, we act directly, otherwise we work with the mainstream systems. Our goal is to hold authorities accountable. All the demands we raise come from direct communication with children and their communities.

Q) In context to the Integrated Child Protection Scheme and the working of Child Protection Committees, what strategies like CPC’s have worked for preventing children being pushed into labour?

Ans: Preventive measures for child labour, have not been very proactive. However, the ICPS is now being proactive and we are working closely with them. In current times, since children are going back home, we have tried to find out how their nutrition, counseling and other needs have been looked after. The model we have proposed focusses not so much on CPC’s, but the existing committees Social Justice Committees under the Panchayats, because we believe in streamlining and catalysing systemic changes in favour of children with the elected Governments . taking responsibility for the children. Only when the matter goes beyond the realm a specific village, do we step it up and approach district authorities. As a part of our work, we have a network of makkala mitras (children’s friends) and mahila mitras (women’s friends), selected by children and women themselves, who are their first point of contact.

Q) Building on the premise that children are become protagonists of their own change, how do you visualize that in the current context?

Ans: This is the core of our work. Our work has been focused on working with and empowering the union of working children. They have been at the forefront of the Karnataka children’s gram Sabhas (2002). Makkala Grama Sabhas are a , which are a milestone and a role model for the entire country now on how children can play a critical role in solving their own problems. Here, children directly talk to their local Governments about their needs and get things progressing. Every Panchayats must have children’s gram sabhas because that is the need of the hour. Enabling adults to listen to children has been fundamental to our work. .

Q) The rights of children as we know it, have turned out to be the largest casualty of the crisis. Your work has used a multi-pronged approach to work in this scenario. Share with us examples on how that has worked.

Ans: During this pandemic, we have worked directly with the elected local Govt. representatives and provided them with inputs about their responsibility regarding disaster management. As a result, we have been able to support the Panchayat Task Forces set by the State to function optimally and to work in consultation with children and community members in a proactive manner.

Our organisation has provided the required information and support to local governments to ensure food, accommodation, health care and such other services are reached to migrant workers who are presently residing in their Panchayats. Where the governance system has been slow to react, the organisation has stepped in to provide the required services, such as food, medicine, transportation etc. too, as an emergency response, while getting the state machinery activated to provide these services in a sustained and timely manner.

We have provided with the State with very detailed recommendations on the following constituencies:

- Children below the poverty line not enrolled in anganwadis or government schools

- Children of migrant communities in transit

- Children enrolled in anganwadis

- Children enrolled in government schools

- Working children and working adolescents

- Children in Child Care Institutions

- Migrant workers (children, women and men) in their place of work & Urban poor

- Migrant workers in transit (children, women and men) to their places of origin

- Workers enrolled under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MNREGA)

- Rural Communities, with a special focus on the most vulnerable such as Scheduled Tribes and Scheduled Castes, persons with disabilities, women-headed households, persons with ailments and elderly above the age of 60

- Gram Panchayats across the state of Karnataka

Here is the link to the recommendations made.

We have intervened at the policy level on several matters including getting the state the recognise all children under 18 as vulnerable groups, getting mid-day meal provision sanctioned, ensuring MNREGA work includes growing of vegetables in the face of the impending food crisis, to name a few.

A report on CWC’s work in relation to Covid19 is available here.